The Future of Sheetfed Offset: What Offset Manufacturer Executives Have to Say

The 2019 Business Outlook report for the printing industry demonstrates just how dramatically the printing industry has changed over the last decade.

The 2019 Business Outlook report for the printing industry (https://store.whattheythink.com) demonstrates just how dramatically the printing industry has changed over the last decade. Average revenues for the commercial printing industry increased by 3.8% from 2017 to 2018 (2.2% when adjusted for inflation), according to the report. This marked the first time in a long time that the value of print shipments exceeded those of the previous year—at least for some months, according to the report. 2018 printing shipments have declined, however, by 19.6% over the last decade, reported at $98.6 billion for 2008, down to $79.3 billion in 2018. WhatTheyThink projects further decline by 2026, to $56 billion.

That being said, respondents to the survey were positive about their near-term prospects. About two-thirds of respondents reported increased revenues, with 42% reporting increases of more than 6%. And almost two-thirds expect revenues to increse by six percent or more in 2019.That’s good news for the industry, and perhaps a signifier that the industry has turned the corner.

Also good news, two-thirds of survey respondents reported at least some increase in profits, with 16% reporting profits that increased more than 10% in 2018 when compared to 2017.

So what is sparking this rise in optimism? The top two best new business opportunities reported by survey respondents were customers outsourcing more work to us (43%) and helping customers integrate print and non-print (37%). Respondents also identified many other opportunities, including offering non-print services; adding wide format, digital printing and package printing capabilities; automating production; and migrating customer service and sales to the cloud, among many more. The report states, “That so many strategic items top the list—especially recognizing the need to help customers integrate print and non-print—is an encouraging sign that we are seeing a new breed of print business leadership that thinks creatively about where print is and where it is going. And that means that companies that survive will likely have a very different mix of offerings by 2026 than they do today.

In spite of the overall optimism, only one percent of respondents cited adding additional offset printing equipment as one of their best new business opportunities. And that brings us to the topic at hand, sheetfed offset printing.

In preparing this article, we spoke to key executives at five companies who manufacture sheetfed offset presses:

- Heidelberg

- Koenig & Bauer

- Komori

- Manroland Sheetfed

- RMGT (Ryobi MHI Graphic Technology, through its U.S. distributor, Graphco)

As you would expect, all of these executives were bullish about their future, and each is taking a slightly different approach to the market. Manroland and RMGT are focused on improving offset efficiencies, while Heidelberg, Koenig & Bauer and Komori, although focused on improving offset efficiencies, are rapidly expanding their digital printing offerings as well. Komori has made the most progress along these lines, with an aggressive 2020 goal of one-third of revenues each from offset, digital and services (KomoriKare). According to Jacki Hudmon, senior vice president of new business development at Komori America, the company is well along the way to achieving this goal. Both Heidelberg and Koenig & Bauer have extended the markets they are targeting. For example, Heidelberg’s Omnifire targets printing on objects, while Koenig & Bauer have digital initiatives for printing on glass, cans and more.

While digital printing technologies still represent a smaller percentage of revenues for Heidelberg and Koenig & Bauer than for Komori, both companies are investing heavily in this area, through internal development, partnerships, and even joint ventures.

In terms of offset press sales, they all see growth opportunities, although a typical new offset press will replace two to three older ones in most cases, resulting in an overall decline in installed base.

Let’s take a look at each, based on our interviews and presented in alphabetical order.

Heidelberg

With its 160+ year history, Heidelberg is the world’s largest offset press manufacturer. The company entered into a joint venture with Kodak in the late 1990’s that resulted in the development of the NexPress digital color toner-based press. Heidelberg ultimately divested itself of the Kodak relationship and went back to its offset roots with a renewed emphasis on packaging, developing its Speedmaster XL 145 and XL 162 platform. During and after the 2008 financial crisis, Heidelberg decided to develop a new strategy for approaching the market going forward. In a recent interview with WhatTheyThink’s David Zwang, Heidelberg CTO Stephan Plenz stated that at the core of its strategy was creating offerings that “support our customers and create more output, while focusing on the income of Heidelberg and the output of the industry.” Part of that strategy required that the company embrace digitization across its product lines. This would include using digital technology to enhance existing offset products, as highlighted by its “Push to Stop” feature introduced at drupa 2016. However, it also included the development and introduction of new lines of digital print technologies to supports customers’ current and future production requirements. This included a partnership with Ricoh for its VersaFire line of toner-based digital presses; the Primefire 106 featuring drop-on-demand inkjet technology powered by Fujifilm using the Fujifilm SAMBA heads; and Omnifire, a direct-to-object printing solution. Heidelberg also acquired Gallus, and the two companies jointly developed the Gallus Labelfire 340, a digital label printer using inkjet technology and with inline finishing for streamlined label production.

These digital offerings are added to Heidelberg’s substantial portfolio of sheetfed offset presses, some 15 different models ranging from 20 inches to its Very Large Format 64-inch press.

The company also offers a complete workflow under the Prinect brand, including a web shop, a suite of production management solutions, a color toolset, business tools and Prinect Production for packaging. The company’s combined hardware, software and services portfolio is arguably one of the most complete offerings from a sheetfed offset press manufacturer. It is this type of end-to-end offering that has led many commercial printers to consider themselves as “Heidelberg shops.”

In its most recent annual report for the fiscal year 2017/2018, the company reported the value of incoming orders (€2,588 million comparted to €2,593 million the previous year), net sales (€2,420 million versus €2,524 million) and an EBITDA of 7.1% for both fiscal years.

We spoke with Clarence Penge, Vice President of Sheetfed in North America for the company, who has been with Heidelberg for 25 years, to get more insight into the company’s sheetfed offset strategy and North American performance. Penge started his career as a pressman in a Chicago commercial printing company.

Penge reports that for Heidelberg, whose fiscal year ended March 31st, sheetfed offset has been a very strong business, especially the last three years. In the North American market for last fiscal year he says, the company’s sheetfed offset business experienced double-digit growth in revenue and added more printing units. Penge notes, “We are by far the largest worldwide at $2.5 billion, and more than $1 billion comes from sheetfed presses.”

Today when Heidelberg installs a new press, it is most likely going to replace two or three installed presses due to the higher productivity and increased automation of these new presses. “As a result,” Penge says, “I see our customers doing well with the new technology, achieving the faster speed to market and lower total manufacturing cost while meeting their customers’ demands. In addition, the newer presses have better uptime, and coupled with our Push to Stop approach where a customer can load all jobs in a queue and take full advantage of the automation, including Autonomous Production , and gain a 15% to 20% improvement in throughput compared to a non Push To Stop press.”

Penge also notes that Heidelberg believes customers need both offset and digital presses. “It comes down to speed to market and cost to manufacture,” he says. “It gives them more flexibility when they operate offset and digital in parallel.” He notes that for most printers, variable data only comprises 10% to 12% of output, and most of it is black only, adding, “Sitting with many customers as they make purchasing decisions, in the end they have to take care of the print buyer. It comes back to speed to market and total cost, which is why there is still good demand for new offset presses.”

Penge is quick to point out that the Heidelberg offering is not just about the output device, but about the entire workflow, stating, “The Prinect suite is the power behind the ability to streamline and automate. The vast majority of today’s offset press components are digital, enabling better management of the press and a streamlined workflow.”

Heidelberg has also launched a unique subscription program as part of its services offerings. Penge says, “We are leading the way on how a customer can get into an offset press. Under the program, the customer gets a new Heidelberg offset press, consulting services, the Prinect suite, consumables, critical training and more with a lower upfront investment. And the investment becomes an operating, not a capital, expense. We set up the equipment and the program based on a detailed analysis of the customer’s work, configuring the press, consumables, training, etc., in order to achieve a target annual volume output. The customer commits to producing a certain number of sheets per year at a fixed cost per sheet. It is typically a 5-year agreement. Because we want customers to overachieve that goal, we provide OEE monitoring and consulting to help drive performance. When they overachieve, it’s a win-win situation for both. . For example a minimum commitment may be 24 million sheets, or 2 million sheets per month. After five years, the customer can renew, return the press or exchange it.”

Heidelberg has just recently launched this program and has several customers worldwide taking advantage of it, including one in the U.S. at the time of this writing. Upfront costs could be as low as 5% of the cost of the press depending on its configuration. “For a customer that hasn’t purchased a new press in 20 years,” Penge is quick to add, “this is less out of pocket than they are spending today on waste and consumables.” He states that in terms of makeready waste, for example, an older press might consume one thousand sheets per job while makeready on a new press can be as low as 75 sheets. “The newest offset presses are doing ultra-short runs of 500 sheets, and sometimes even have a cross-over point as low as 75 sheets,” he adds.

Penge concludes, “Fifteen years ago, I never would have imagined we would have had such a robust portfolio. We were really happy when the company partnered with Ricoh, Fujifilm, MK and others. With Fujifilm, for example, we get access to the best inkjet heads into which they have invested 10 years of research and development instead of waiting to develop it ourselves. We are using all of our resources, including partnering and our own R&D dollars, to improve speed to market for our customers. In the end, that’s what it's all about.”

Koenig & Bauer

As we were preparing to interview Koenig & Bauer President and CEO Claus Bolza-Schünemann, we received a copy of the company’s customer newsletter, which is published three times per year. In this issue (#54), which is comprised of 60 pages primarily dedicated to stories about how customers are using – and growing their businesses with – Koenig & Bauer technology, Bolza-Schünemann reports that 2018 was another successful year for the company, which is now 201 years old. The company distributes 35,000 copies of this report to customers and partners, an impressive distribution.

The company, whose tagline is “we’re on it.”, reports that despite challenges in 2018 that included bottlenecks in parts availability, long lead times, as well as expected disruptions caused by implementing SAP, Koenig & Bauer reported the highest EBIT in its 201-year history, with a gross profit margin of 29%. Revenues increased slightly from €1,217.6 million in 2017 to €1,226 million in 2018. The company entered 2019 with a high order backlog of €610.9 million. Bolza-Schünemann is quick to point out that the company has cash in the bank and no debt. The company projects organic growth of up to 4% for 2019 with an EBIT margin of around 6%.

Digital and web comprised 12.3% of corporate revenues in 2018, amid an expanding digital portfolio. Slightly lower digital revenue as compared to 2017 was attributed to fewer installations of the HP PageWide T1100 press for corrugated pre-print, which is manufactured by Koenig & Bauer and includes components provided by HP.

Service offerings contribute about 25% of revenues, while new equipment sales represent about 75% of revenues. The lion’s share of new equipment sales (70%) comes from packaging applications, which include sheetfed offset, flexo, glass and metal décor; 20% comes from security printing and 10% is in media, including newspapers and magazines.

Koenig & Bauer is the only company in this group that offers flexographic printing solutions, which comprise about 6% of new machine business. The company builds about 1,600 sheetfed offset units per year, starting early with castings and cylinders, putting the final machine together based on customer specifications.

In terms of its services business, Koenig & Bauer offers ten different packages ranging from regular check-up maintenance to performing full service for the customers. The company offers smartphone apps that allow customers to look at the press while the machine is running to assess speed, net speed, net output, last plate change and operators can even activate press functions via their smartphone. Customers can also compare performance amongst multiple presses in the plant, as well as anonymously against other customers running similar work that allows them to benchmark their performance and take any necessary mitigating steps to improve.

For industrial continuous inkjet printers, Koenig & Bauer partnered with a university to introduce artificial intelligence called Kyana, to allow customers to communicate via voice assistant with the printer and monitor, showing with augmented reality everything that happens inside the printer. “We have thousands of these Coding inkjet printers usually installed in food packaging lines, placing dates and barcodes on different packaging surfaces,” Bolza-Schünemann explains. “If anything happens to those printers, the whole production line is down.” Therefore, Kyana acts as a virtual Koenig & Bauer assistant and helps autonomously to minimize downtime, take countermeasures and ensure the fastest support available.

Using data glasses and virtual reality for sheetfed and web machines enables an operator to connect live with Koenig & Bauer’s online support wherein both parties can view what is happening and work together to resolve any issues. Besides data glasses, a smartphone can also be used to collaborate with technical support to jointly view electronics and wiring, download wiring diagrams and much more. This minimizes the need for travel and helps customers get back up and running quickly. Two-way communications between equipment and service also enable predictive maintenance, updates and upgrades, further reducing potential downtime.

Koenig & Bauer continues its 8-year partnership with RR Donnelley around its RotaJET line of presses for digital décor and packaging printing. Recent RotaJET sales include Interprint and TetraPak.

The company also announced its first-ever joint venture, a 50/50 arrangement with Durst for the joint development and marketing of single-pass digital printing systems for the folding carton and corrugated fiberboard industry. Initially, the joint venture portfolio will comprise the Koenig & Bauer CorruJET 170 and the Durst SPC 130 – including all associated services and the ink business, with a top priority to develop the VariJET 106. The VariJET was first announced at drupa 2016 in conjunction with another partner; this partnership has been amicably disbanded and product development proceeds with Durst instead. While Durst also has a textile printing business, Bolza-Schünemann stated that Koenig & Bauer has no plans to enter that segment.

Other digital printing applications, including printing on plastics and glass, have been introduced by Koenig & Bauer Kammann as well.

Bolza-Schünemann concludes by saying, “This is a beautiful business we are all in. Many people believe that with digitization, you don’t need print anymore. But both nature and mankind live only by physical, not digital, things. Packaging for food and drink, clothing, wallpaper – everything is printed. I am absolutely convinced that the printing industry has a very long and very good future. That being said, no business runs forever as is. We are 201 years old and looking ahead to 300. We are always looking for new applications and niches linked to our core competency of putting inks on any substrate.”

Komori

Of all of the sheetfed offset companies we spoke to, Komori has the most aggressive digital strategy. According to Jacki Hudmon, senior vice president of sales and marketing at Komori America, “Over the last three years, Komori has redefined what the company will look like by 2020, transforming our business so one-third is offset, one-third comes from services (KomoriKare) and one-third is inkjet. We will be close to achieving that in 2020.” To ensure a smooth transformation, Hudmon is overseeing all sales and marketing. “This way we don’t have someone doing digital and someone else doing offset,” she explains. “We are approaching the market more holistically, selling output and devoted to building solutions for our customers, now and in the future.”

There are still some challenged with sales, Hudmon admits. The company has overlaid inkjet specialists – solution architects – to help conventional sales people deal with the newer technologies. “At the end of an analysis of a customer’s business, if the answer is not a press, we don’t want them to be motivated to recommend a press if it’s not the right solution for the customer.”

“The biggest sales issue we have,” she continues, “is that we have great brand recognition in offset. Even though we have been quietly working on inkjet for two decades, it is challenging to transfer that brand recognition to inkjet. When it comes down to it, inkjet is a printing press; it’s what we’ve done for 100 years.”

Hudmon points out that the company and its processes have been geared around offset printing for a century. “Now we are selling ink and consumables and other products and services,” she says. “You can’t process those in the same way you would process a $2 million press order. So we are also changing our infrastructure to accommodate that.”

On the digital side, Komori offers the Impremia IS29 UV inkjet press, continuous feed inkjet from Screen, and the Impremia NS40, Komori’s version of the Landa Nanographics press. “We believe we have all the bases covered,” Hudmon notes.

She points out that there is a lot of consolidation in the current market for offset, and the company has focused on value add in that arena. Hudmon cites the Lithrone GLX840P, a brand-new press platform which delivers cured sheets ready for finishing at the end of the press at 18,000 sheets per hour, noting that 80% to 90% of the presses Komori is selling have some UV or LED curing on them. “You take someone that has three conventional presses, and they have instant savings by moving to a streamlined workflow.” The benefits of this type of consolidation in the pressroom are resulting in new press sales, she states, noting that many customers are putting double coating on their presses, especially for applications like direct mail, making the pieces more tactile for their customers. “These two areas are the primary drivers behind our offset press sales,” she adds.

Hudmon recently returned from the Inkjet Summit, where I.T. Strategies’ Marco Boer predicted that 2026 would be the tipping point where inkjet would make an impact on offset. “At the Summit, you heard all of the panelists and everyone talking about how they are using inkjet as an offset replacement, what they are doing with inkjet, what they are saving in terms of crew or shifts on an offset press, and how they are going to sell programs and variable data,” Hudmon comments. “But when you talk to a lot of commercial printers, they don’t have the data knowledge to get there yet. Every vendor tries to help them get there faster, but they need to come around on their own. We’ve seen good adoption of the IS29 UV inkjet press for a variety of applications. We put a lot of energy into developing a business development kit demonstrating the breadth of applications that come off the IS29 – there are very few limitations as far as substrates. Commercial printers wanting to get into digital love it, because they can print on anything and it is unique in that respect. Some are also driving new business they couldn’t do before. But it’s not a true offset replacement for a press like the GLX40.”

Hudmon reports that Komori will be launching the NS40 at drupa 2020. It’s a 7-color digital press that runs at 6,500 sheets per hour and can print on any substrate up to 32 point. “When Marco talks about the tipping point, it will be presses like the NS40 that will help get to that tipping point,” she says. “It uses an EFI front end, SAMBA heads and is targeted at packaging and point-of-purchase applications. It is a distinctly different product with unique differences from the Landa version.”

Hudmon cautions buyers, though, saying, “You shouldn’t be looking at whether to buy offset or digital, but rather, looking for a solution that meets your needs. Komori is a solutions provider. We want to go in, analyze a customer’s business and help them make the right decisions. They are stuck right now, having issues finding skilled labor, having three crews running 24/7 on older presses, asking, ‘should I wait or consolidate my pressroom?’ Now more than ever, a wrong decision is lethal, and that’s where we can help; looking at the entire production process, identifying bottlenecks, understanding where they want their business to be in three years. With drupa next year, it will be more confusing than ever. In the end, it might not even be a Komori sale. It could be that finishing or MIS is the bottleneck today. If they don’t do anything, they will be in jeopardy, and our goal is to help them find the issues and keep moving forward.”

Thus, Komori continues to work with customers to educate them and help them make better decisions. “It’s pretty impactful when you show a commercial printer the variety of work you can do with inkjet – direct mail with variable data, handicap placards, menus – they quickly realize they have been walking by these opportunities and can drill deeper into existing accounts, becoming a single source, by leveraging both offset and digital.”

On the service side, Komori is rolling out KP Connect this year, a cloud-based subscription solution to help drive greater efficiency in the pressroom. “This includes interfacing with or integrating with JDF workflows and an MIS, mostly EFI,” she explains. “It’s also part of our infrastructure adjustments to the transformation. Now we can be more proactive about servicing, uploading data to the cloud every 30 minutes, doing monthly calls.” Hudmon says they might alert a customer that their OEE has slipped or their waste is higher. “We use this as a tool to help our customers focus on the details,” she says. “Details are huge.” She cites one large web-to-print customer Komori has been proactively working with, saying, “As one of the most efficient companies in web-to-print that I thought was doing everything right, we have been able to drive significant savings for them. Even cutting out a few percentage points of waste is significant.”

Hudmon concludes by saying, “Even though the U.S. market for offset has flatlined, which is true for all of the manufacturers, emerging markets are still growing. We just established our first subsidiary in India, and it’s gaining great traction. China is softening, but India is picking up the slack.”

Komori, whose most recent fiscal year reporting as of this writing is for the Fiscal Year ended March 31, 2018, reported a 9% increase in net sales, and almost doubled its operating income. In North America, net sales for FY2018 were down, $80 million in FY2018 compared to $93 million in FY2017, with net sales for FY2019 projected to be flat at $80 million. Worldwide, sheetfed offset presses represented just over half of net sales. The company projects a 9% increase in sheetfed offset sales worldwide for FY2019.

With its aggressive digital and services strategies, yet still bringing new and improved offset platforms to market, Komori is well positioned to continue its growth into the future.

Manroland Sheetfed

Manroland’s history goes back to the mid-1800s, and the company was a key player in the offset printing industry, ultimately offering both web- and sheetfed presses. In 2012, following a filing for insolvency in 2011, the company split into two entities: manroland web systems was sold to the German L. Possehl & Co. mbH, while the sheetfed division, which is the subject of this profile, was purchased by British Langley Holdings plc in February of 2012 and became known as Manroland Sheetfed GmbH. In March of 2012, Manroland Sheetfed and Landa Corporation announced a strategic partnership whereby Landa would provide Manroland Sheetfed with its nanographic printing technology, although to date, no products have emerged from this partnership.

Today, Manroland Sheetfed operates as a subsidiary of Langley Holdings, whose 2018 financial report reflects corporate revenues of €848,387,000, down from €903,529,000 in 2017. Operating profit was also down slightly. The parent organization employs 4,255. The company has cash in the bank and no debt.

For the Manroland division, Langley reported revenues of €259.9 million, down from €286.3 million in 2017. Manroland Sheetfed employs 1,520. Langley attributed the revenue decline in part to tensions between the U.S. and China, causing orders from China, Manroland’s largest market, to plummet. Despite that setback, Langley commented in its annual report:

… the division contributed only nominally to the overall group result in 2018. However, it was a positive contribution, and after non-recurring costs of around €2m to reorganise the European market organisations. Despite this, and much more substantial reorganisation costs in the early years of our ownership, the business has stood on its own feet financially since it was acquired, and our initial investment has been more than recouped. The company has also been investing heavily in new product development and the company’s ROLAND 700 Evolution press, developed entirely during our stewardship, is now widely recognised as “best in class”.

Langley expects a positive contribution from Manroland Sheetfed in 2019, although not a significant contributor to the group. Another interesting nugget from the Langley report regards the German manufacturing facility, which has a manufacturing footprint of over a million square feet that is “significantly underutilized.” Langley reports it continues to search for a “suitable bolt-on acquisition for this state-of the-art facility and world-class sales and service organisation.” That will be an interesting search to watch.

At this time, Manroland Sheetfed CEO for the U.S. and Canada Sean Springett states that the company is not working on any digital initiatives, or at least none they are willing to discuss, which leaves open the question as to whether the Landa partnership is still active. He does point out, however, that when Landa first announced the Nanographic concept in 2012, the product was designed to fill a gap that existed between digital and offset. “Since then,” Springett states, “digital has crept up in efficiency and so has offset, making the gap much smaller, if there is a gap at all anymore.”

With respect to digital, Springett commented, “We firmly believe that the issue on digital implementation, incorporating digital into an offset platform, is an issue of ROI. Digital isn’t running at a fast enough pace where we see there is an industrialized application yet. Technology-wise it exists on the bleeding edge as a cool factor. But until these inkjet solutions increase in speed to complement an offset press, we find it difficult to justify. A printer could spend $3, $4 or $5 million for a press that is limited to running at 4,000 or 5,000 sheets per hour based on a big industrialized piece of machinery that is meant to run at 18,000 sheets per hour. We think there is more maturation that needs to occur on the digital side for a hybrid offering, and that for now, it is better to have a separate digital press in combination with an offset press.” When asked about a timeline to make a hybrid solution feasible, Springett replied, “Maybe 5 to 10 years out, and we are not being asked about that by customers.”

Springett points out that when production inkjet first hit the market 14 years ago, there was a great deal of discussion about how the technology would replace offset as a more economical platform. “The reality,” he states, “is that 84% of print is still industrialized as we know it from the past, with modernization in traditional offset application, while digital comprises only about 16% of the volume.”

Manroland efforts, then, are directed toward pushing the envelope on the offset side to further increase efficiency and make it more profitable. Springett reports that this strategy is working, citing the sale of two offset presses in the last year against digital alternatives – in other words, the acquisition process started with the intent to purchase a digital press, yet the customers ultimately chose offset because their primary goal was to produce short runs, not variable data work.

In terms of offset efficiency, Springett notes that the company has customers printing with a makeready waste of between 65 and 150 sheets, with a good-sheet-to-good-sheet changeover time of 13 to 20 minutes, adding, “You can cycle through a lot of work like that.” The relevant cost factor, he states, is the cost of plates. “Aluminum plates continue to be very economical relative to the cost of print, depending on your ability to purchase in a reasonable volume.,” he says. “But digital is pushing all of us to squeeze as much efficiency as possible out of offset.”

Manroland introduced its new Evolution press into North America in 2017. The press, according to Springett, featured more than 254 changes and brought a large shift in Manroland capability, including color control that provides a better ROI in comparison to the previous product line; and the uptake in North America has been good, according to Springett.

Manroland does compete against Heidelberg, Komori and Koenig & Bauer but is a significantly smaller company. “As a result,” Springett says, “we are far more of a niche player in the market, and we have a tendency to develop and find markets and accounts where the type of technology we bring fits well. Where we spend most of our R&D time is figuring out how to achieve the highest net productivity.”

To that end, 90% of output from Manroland presses is packaging in North America – largely folding carton and pharma – while 10% is general commercial printing. In pharma, Manroland customers produce pharmaceutical inserts printed on light onionskin, primarily black over black, as well as blister packs and folding cartons. “Pharma has a very high demand for quality control,” Springett says, “with every sheet checked with a PDF checker and an inline 4K camera.”

In commercial print, Manroland typically installs a 4/4 press with perfector. “We are also seeing more demand for inline capability, what we call a one-pass press,” Springett says, “especially in packaging where we often see inline units that print, coat, dry, perfect, print, coat, dry and deliver. We also see packaging applications where there are two to three coaters with print units between the coaters. Just about every press we sell is custom, with an average order lead time of six months from order to delivery. And that customization is one reason we have not come to market with any kind of subscription plan. We don’t believe the subscription model works well in the grand scheme of things. Our market clientele often possess what we would call black book knowledge; they are printing with chemistries they themselves have put a lot of time and money into, figuring out the right combination to ensure successful print applications for their client needs. It’s difficult to duplicate that in a model where the presses and chemistries are custom built.”

Manroland does, though, have very close partnerships with its customers. “Where my team and I spend a large portion of our time with customers,” Springett says, “is in helping them improve the productivity and performance of their presses. Today’s presses all come with production analytics tools. In North America, through a program called ProServe 360, we monitor the presses and generate a 19-page report for each customer every 30 days to minimize the risk of things getting too far out of control. It gives us a good snapshot of what is occurring and allows us to correct issues quickly so we don’t end up losing 25% in a year waiting for a quarterly report. In fact, we put in just as much effort with our customers post-sale as we do pre-sale.” The ProServe 360 program is mandatory for Manroland customers for two years, and extension to a third year is optional but highly recommended.

As with other offset press manufacturers, Manroland Sheetfed sees two to three older presses being replaced by each new one, as well as cost-effective run lengths for offset declining to 250 to 500 sheet runs. This makes the decision process for buyers foggy, he notes, and with drupa 2020 coming up, it is likely to get even foggier, depending on what new technologies are shown there!

RMGT (Graphco)

Ryobi MHI Graphic Technology, or RMGT, was formed in in 2014; Ryobi Limited has a 60% ownership stake, while Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Machinery Systems owns 40%. Both of these companies were founded in 1943. In 1961, Ryobi began manufacturing offset printing presses, while Mitsubishi brought its first offset printing press to market in 1962. With a long-term outlook on the offset printing industry that indicated there would not be enough business for everyone by 2025 or 2030, the two companies decided to come together while both were strong.

In 2018, Ryobi LTD elected to move from the traditional May 1 fiscal year to March 31, making FY2018 a 9-month year for reporting purposes. According to Manley, had the three additional months been added, revenues would have been up 2% to 3% over the previous year for printing equipment. In FY2019, revenues for printing equipment came in at $250 million with a net income of $5.4 million.

At drupa 2008, Ryobi introduced an LED-UV printing system, the first such system for sheetfed offset printing and a technology that is now widely in use. As the story goes, a Ryobi engineer accompanied his wife to a nail salon, where he saw gel nail polish being cured using cool UV LED light. That sparked an inspiration about LED usage for curing of ink, and the rest, as they say, is history. The technology was quickly adopted in Japan, and by 2010 there were more than 100 placements. “Waiting for things to dry has been the bane of the offset manufacturing process for a long time,” stated Chris Manley, President of Graphco, the RMGT distributor for 17 states.

The RMGT Series 9 UV LED presses were also launched at drupa 2008 and have been a mainstay of the company’s business in North America, according to Manley. “Our messaging to the market” he notes, “was that this press allows you to produce an 8-up sheet but do it 30% to 35% less expensively than competitive 40” presses. It took us a couple years to get the message through to the market. At first, we were mostly in a defensive posture, having a smaller sheet size, but that has now shifted to customers telling us that’s what they want. It is notable that of the 30 Series 9 presses we have installed in our territory, only three have a pressman and helper; all of the others are operated by a single pressman.” Manley reports that to date, RMGT has installed nearly 800 of these presses worldwide.

The Series 9 presses are highly automated, according to Manley. “In 2003, 10,000 sheets was considered short run in offset; by 2005, that number was 7,000, way down from 30,000 in the 90’s. Now, with instant curing and overall efficiency, it has allowed many of our customers to run these presses like a big digital press, other than the fact it doesn’t do variable, which is only about 10% of the market anyway. Customers now are profitably running jobs as small as 250 to 350 sheets.”

Manley cites one customer who had three digital presses and two conventional presses. He acquired a 6-color 9 Series RMGT press and was able to sell both conventional presses and two of his digital presses. “He feels he is able to run his business with one Series 9 and one digital press. He can turn around four short runs of 350 or 500 sheets on the Ryobi press in as little as 10 to 20 minutes with better quality than the digital press. I don’t think there is a digital way to produce 1,000 or 1,500 sheets for less than we can do. Its stability is a safe place for our customers, too.”

It is worth remembering that Ryobi does have a digital heritage, having developed the DI press that Presstek sold. Ryobi was also the paper handling part of the original Indigo press, along with being an OEM provider to a number of other technology companies. “In these partnerships, information flows both ways,” Manley states. “That has resulted in a significant amount of artificial intelligence being incorporated into the presses in the form of algorithms that promote machine learning. It’s a big part of why someone can sell a 4-up 350-sheet job and only use 50 to 75 sheets to get up to color.”

Manley reports that sales are booming, saying, “We grow every year by double digits. By the middle of April 2019, we had sold and booked as much equipment as we sold and booked by the end of the second quarter of 2018. Last year it felt like we were on a roller coaster ride; this year feels even more so.”

RMGT in North America is also experimenting with augmented reality (AR), using it in its own marketing efforts to show the muiltimedia relevance of print while supporting the AR experience. Visitors to the RMGT booths at Print 18 and SGIA were able to experience this first-hand.

RMGT, then, is focused on taking advantage of what it sees as a healthy market for the offset presses it is manufacturing, and the company has no publicly stated plans to introduce a digital or hybrid press to the mix in North America. Manley stated that Ryobi would be introducing some “cool new offset-related things at drupa 2020, big improvements that will make our offset presses even more viable in a short-run digital world. Our philosophy is how do we coalesce in a digital world instead of adopting a digital platform and trying to outsell HP and Xerox. I feel good about the fact that we are putting most of our eggs in the offset basket.”

Conclusions

The three largest manufacturers of offset printing equipment have aggressive digital initiatives underway, balancing what they see as a flat to declining market for conventional offset presses with digital alternatives and a diversified portfolio. The two smaller companies have focused their attention on improving productivity, efficiency and customer profitability with conventional offset and have not disclosed any digital initiatives publicly.

Over the past few years, manufacturers have made significant progress in improving offset press performance. While digital presses have moved up the scale in terms of the cross-over point with offset, offset presses have come down, with manufacturers claiming offset presses are effective for static printing of as few as 250 to 300 sheets per job, with highly automated fast changeovers between jobs and minimal makeready waste. Thus, for printers looking to invest in a new printing press, it is critical to examine the current job mix and determine where the company wants to be in the next few years. This will help determine whether a new press investment should be offset or digital and what the balance between the two should be in the company’s production portfolio. All of the manufacturers are well positioned to help with this analysis. Komori, for example, states outright that the analysis may show there is no need for any additional Komori products, and the company has structured solution architect compensation to ensure agnostic results are delivered to the customer.

Although our survey reported that only 1% of respondents saw acquiring an additional sheetfed offset press as a new business opportunity, it is possible respondents interpreted the question in a variety of different ways. Typically, according to all of the manufacturers we interviewed, a new offset press replaces two to three older ones due to the performance improvements new presses embody.

Of course, all of the companies we interviewed were bullish about the value their respective offerings bring to the market and their relative positions in the marketplace. As the commercial print market (NAICS 323) continues to consolidate, printing companies are seeking new revenue streams and new applications. The diversification we see in the three largest companies is well positioned to help them get there.

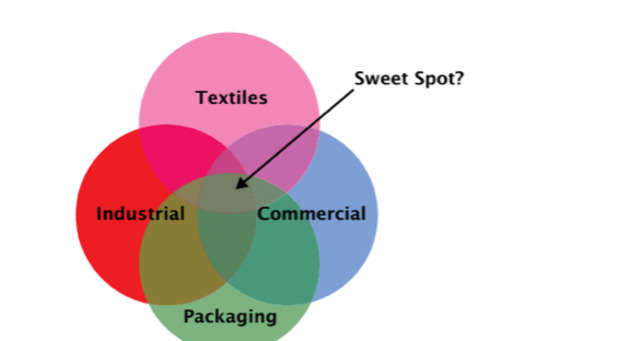

In the WhatTheyThink Printing Outlook 2019, author Richard Romano points out that there is, in some sense, a convergence among various printing categories, most of which are not included in NAICS 323.

For printing companies, there are plenty of opportunities for growth in what Romano has designated the Sweet Spot of convergence, areas of overlap that we often call specialty printing, as well as digital décor such as wall coverings, promotional items produced using heat transfer dye sublimation, textiles and more. Packaging, of course, is a growth area that is being pursued by offset press manufacturers and their customers alike. Heidelberg offers direct printing on 3D objects; Koenig & Bauer have solutions for printing on glass and cans. None of the five players we interviewed, however, are pursuing textile applications, at least not at this point – or not that they are talking about. However, on the digital press manufacturer side, this is a hot area.

Another discipline that is gradually making its way into printing companies is 3D printing, so far primarily in a small number of companies in signs & display graphics and promotional products. But we expect that to gain traction over the next few years as well.

When we look at the industry from a more macro perspective, then, there are plenty of opportunities for growth. Clearly, sheetfed offset and digital will coexist for some time into the future. Paraphrasing Mark Twain, the reports of the death of offset are greatly exaggerated.

For manufacturers of offset presses, diversification is one approach and finding niches is another … for printing companies, it is important to take a strong and strategic look at the current state of the business, have a plan in place to take it to the next stage, and then find the right vendor partners to get you there.

We hope this report is helpful to both!