Blurred Lines: Gotta Give it Up for Apparent Resolution

The fundamental question is: when shopping for printing equipment, is “apparent resolution” meaningful?

If you are ever at a Graph Expo or Print and want to play hooky (à la Ferris Bueller), head over to the Art Institute of Chicago. One of the museum’s most famous works is Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte–1884, the archetypal example of Pointillism, a style of painting that creates an image using tiny dots of color. The canvas is 81.75 by 121.25 inches, what we might call “grand format.” Look at it up close; from a foot or two away, you can easily see all the dots. But as you move further away, the dots become less visible until, by the time you’re across the room, the painting looks for all intents and purposes like a continuous-tone image. I don’t know that anyone has calculated the “resolution” of Seurat’s painting—he was using a paintbrush, not a tiny inkjet nozzle, and as far as I know, art critics don’t evaluate paintings by the number of dots per inch—but as you can tell, the perceived quality of an image is subject to a number of variables.

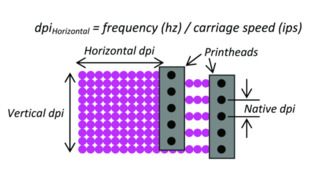

It would seem straightforward: the smaller the dot that a machine can produce, the more dots you can fit in an inch, the greater the resolution, and ergo the greater the quality of whatever is bring printed. QED—not. While image quality can generally be assessed by the numbers, it’s more complicated than that. Not all dots are created equal, and the quality of an image depends on factors beyond simply the number of them. It’s also dependent upon how those dots are arrayed, as well as external factors such as the viewing conditions of the final print. The latter is a common issue in wide-format printing: a print designed to be seen from a distance of five feet, 10 feet, or even further in the case of signage, posters, and certainly billboards, will have a higher “apparent” resolution than, say, an image designed to be viewed up close, like a photograph in a magazine, catalog, or direct mail piece.

When you’re reading printing equipment spec sheets, you often come across two (at least) measures of resolution: actual and apparent. (Sometimes they are called different things.) The first one is easy to grok: sometimes referred to as “addressable resolution,” it’s a quantitative measure of what a machine is physically capable of. The second one is more qualitative: it’s what the output seems like, or can simulate. It’s kind of like a straight thermometer reading vs. wind chill: what is the physically measureable temperature vs. what does it “feel like” outside?

There is a historical basis to the notion of apparent resolution.

“In my past, when I worked with digital continuous-tone photo-printers such as the Cymbolic Sciences Lightjet printers in the 1990s,” said Randy Paar, Marketing Manager at Canon Solutions America, “we needed a way to describe the degree of quality relative to offset printing and the conventional halftone screening and related dots per inch of imagesetters. When variable-drop printing emerged in the large-format inkjet market, comparisons between its improved image quality vs. fixed-drop printing were not appropriately addressed simply by quoting a ‘dots per inch’ resolution specification.”

The fundamental question becomes: when shopping for printing equipment, is “apparent resolution” meaningful, or just marketing flimflam?

Speaking qualitatively, “resolution” refers to how sharp an image is, or how much detail an image contains. There are many factors that determine how sharp a printed image can be. The output device’s addressable resolution and its nozzle count are really only a starting point, which is why a 1200-dpi printer may not print as well as, qualitatively speaking, another 1200-dpi printer—or even a 720-dpi printer. (By the way, although the “apparent resolution” issue applies to just about any digital printing—or it could be argued, any printing—we will limit this article to digital inkjet printing.)

Some of these variables include:

Dot placement—Divide the original artwork into a very fine grid, and then create a corresponding grid on the substrate—like the board game Battleship. Whatever is in square E17 on the original—a dot or no dot—should appear in square E17 on the substrate. So to what extent can a printhead accurately accomplish that—i.e., sink your Battleship? Think about all the things that can affect the trajectory of a liquid droplet measured in picoliters, and that becomes part of the apparent resolution equation.

Variable dot/drop size—In offset printing, unless you are using stochastic screening, a halftone image is composed of many dots of different sizes. Small dots in highlights, large dots in shadows, and a mix of sizes in the midtones. Many of today’s digital printing devices likewise use different dot sizes, or some variation (as it were) of variable-dot-size technology, with which complex algorithms in the RIP determine what size dot should be placed in which location to provide optimal output quality—again, apparent resolution. So the combinations of different sized dots is another piece of the equation, and is largely the reason we see the term “apparent resolution” today: by definition it cannot be expressed as a single, empirically measured number.

Number of colors/inks—When printing with a four-color (CMYK) device, there can be bit of graininess in the quartertones. However, adding light cyan and light magenta can fill in these areas, reduce the graininess, and boost the perceived resolution of the image. Even more colors—light black, for example—can add even more shades of gray (if you’re into that). So the number of colors you are printing can also impact the apparent resolution or the perceived quality of an image. Making this even more complex is that a four-color system that uses variable-dot imaging may solve the quartertone graininess problem better than a six-color fixed-dot system. (It can all make your head explode, can’t it?)

Number of passes—Aside from single-pass printers, most inkjet output devices go over the same line of dots more than once, filling in additional detail and compensating for any clogged nozzles or other mechanical issues.

Substrate—What you are printing on is a bi-i-i-ig determinant of perceived image resolution/quality. Dot gain can result in a “softer” look to a print and plug up some details, or, alternatively, in some cases, it can boost perceived quality by reducing graininess. And as we all know, different substrates cause different levels of dot gain. So whether you are printing on an uncoated or a coated paper—and all the different grades thereof—will affect your apparent resolution.

Viewing conditions—Of course, there are the conditions in which the image is meant to be seen. This is not just the viewing distance, but also the ambient lighting and other environmental factors—even the eyesight of the person doing the viewing.

Target application—Last but not least, what is the actual end-use product that’s being printed, and what is the acceptable apparent resolution? Architectural drawings, engineering diagrams, and transactional printing have different requirements than retail/POP graphics, luxury packaging, high-end publishing, or direct mail, for example. So depending on what you are printing, a very high resolution—actual or apparent—may not even be necessary or, given how file size and processing time increase with resolution, desirable.

There is no shortage of mathematical equations that will calculate “effective resolution” based on addressable resolution and one or more variables. Ultimately, though, when it comes to the resolution game, don’t get too hung up on the mathematics of it all, because your customers won’t. Image quality is quite literally a qualitative assessment; a printed image either looks good and is acceptable, or it doesn’t and isn’t, and there’s very little on a spec sheet that will allow you to easily determine this. The best practice when evaluating print engines is to view actual output—your own output—on materials and under conditions that will likely be used in your production. You can use apparent or effective resolution figures as a starting point for further evaluation, but understand that “your mileage may vary.” No, it’s not all marketing flimflammery, but neither is it a definitive quantification of quality.

When it comes to visually perceived materials, numbers may not lie, exactly, but they won’t tell you the whole story. Your own eyes—or those of your customer—will. And it’s your customer’s perception that will be the final arbiter of apparent resolution.